Woke 2.0?

The Next Turn of the Ideological Pendulum

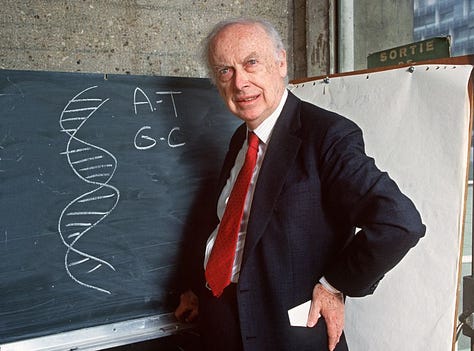

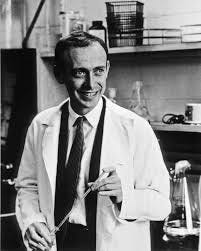

In Memoriam: Dr. James D. Watson (1928–2025)

This article is dedicated to the memory of James Watson, who passed away today. As one of the co-discoverers of the DNA double helix, his groundbreaking contributions transformed our understanding of genetics and laid the foundation for modern molecular biology. His work continues to shape the very debates about nature and nurture that this essay explores.

Are we about to get a sequel to the “Woke” era? It’s a question popping up in many circles lately. After the rise of a brash “edgelord” counter-culture reacting to Woke excesses, some speculate that an equal and opposite Woke resurgence is just around the corner, as if culture swings back and forth like a metronome. On the surface, this cyclical thinking is on the right track. History does tend to move in waves rather than a straight line. But focusing only on the last few years is too narrow. The Woke era of 2016–2020 wasn’t just an isolated spasm destined to repeat in short order; it was the crest of a much larger historical cycle, one that stretches back over 80 years and arguably even to the Enlightenment. To see what might come after Woke, we have to zoom out and look at the long pendulum swing between two grand narratives of human difference: “nurture” vs. “nature.”

This Article was inspired by SirDoug:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Enlightenment Roots: Nurture over Nature

The debate over why human groups differ, in behaviour, achievement, or social outcomes is centuries old. Enlightenment thinkers of the 17th–18th centuries largely championed the primacy of nurture (environment and upbringing) over nature (innate traits). This era embraced the notion of the mind as a tabula rasa or “blank slate”, empty at birth and moulded entirely by experience. A key philosophical backdrop was Cartesian dualism, René Descartes’s sharp separation of mind and body (res cogitans vs. res extensa). Descartes’ “radical division between body and soul” suggested that our true selves (minds or souls) exist independent of our physical biology. Such dualism laid groundwork for the idea that human nature is highly malleable: if the mind is a disembodied “ghost in the machine”, it might be shaped by education or reason rather than bound by heredity.

Thinkers like John Locke ran with this idea. In 1690, Locke argued that the human mind starts as a blank slate and that all knowledge comes from experience. He even mused that if a Native American leader (the “Virginia King” Apochancana) had been educated in England, he might have become “as good a mathematician as any” Englishman. In other words, give everyone the same upbringing and you’d get the same results. This was a radical egalitarian stance for its time. (Locke himself was no modern progressive, he infamously wanted to outlaw atheism but his blank-slate theory became a pillar of liberal thought.)

By the mid-18th century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau pushed the nurture-first view even further. Rousseau is often seen as an intellectual forefather of today’s left. He believed humans are born good and equal, a “noble savage” in the state of nature and that it’s society that corrupts and creates inequality. In his famous opening to The Social Contract, Rousseau proclaimed, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” He blamed social institutions for greed, envy, and vice, asserting that if you strip away civilisational artifices, human nature is essentially virtuous and the differences between people will be trivial. This ideal of inherent human goodness and equality, constrained only by oppressive social chains, was a proto-“woke” idea long before the term existed.

Enlightenment-era science also leaned toward explaining differences via environment. The (now-discredited) theory of Lamarckism posited that organisms could pass acquired traits to offspring, implying effort and environment could directly alter heredity. Such views upheld that nurture trumped nature. By the 19th century, this faith in environmental determinism reached a high. In 1848, British philosopher John Stuart Mill admonished that it was intellectually “vulgar” to attribute group differences to inherent traits. “Of all vulgar modes of escaping from the consideration of the effect of social and moral influences on the human mind,” Mill wrote, “the most vulgar is that of attributing the diversities of conduct and character to inherent natural differences”. In Mill’s day, some argued (for example) that the Irish were naturally lazy or inferior, Mill blasted such claims as ignorant excuses to avoid looking at social causes. His view (shared by many reformers since the Enlightenment) was that with the right education, culture, and opportunities, all groups would fare the same. This was essentially the egalitarian creed, human differences come from external circumstances, not inborn abilities.

The Darwinian Reversal: Nature Strikes Back

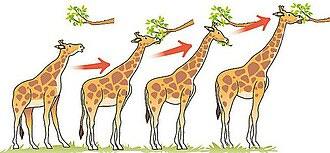

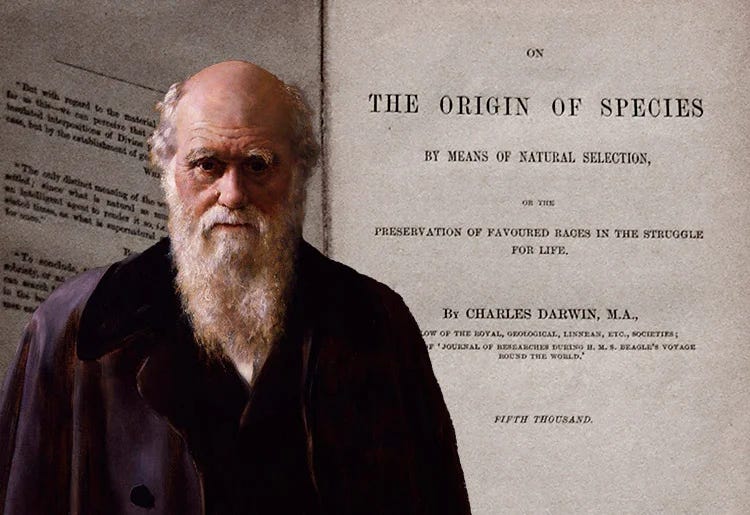

But intellectual tides turn. Later in the 19th century, especially after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, the pendulum began to swing the other way. Darwin’s ideas about natural selection and heredity sparked a surging interest in biological determinism. Suddenly, scientists and social theorists found “nature” explanations compelling: maybe differences between classes, nations, or races stemmed from innate, evolved traits after all. By the late 1800s, theories of racial hierarchy and eugenics (selective breeding of humans) gained traction, and “Social Darwinism” was born. This was an intellectual movement that applied “survival of the fittest” thinking to human societies, often with controversial implications.

Under Social Darwinism, inherent genetic differences were used to justify stark inequalities. In politics and economics, it provided ideological cover for both laissez-faire capitalism and ethno-nationalism. Captains of industry in the Gilded Age invoked “survival of the fittest” to oppose social welfare, implying that aiding the poor or regulating business would interfere with natural selection in the marketplace. At the same time (and at the opposite end of the political spectrum), racial theorists seized on Darwinian ideas to argue that some races or nations were biologically destined to rule over others. This strain of Social Darwinism paved the way for fascist ideologies in the early 20th century, which glorified the “strength” of a superior race and had contempt for the “weak.” In short, by the 1920s–1930s, the pendulum had swung to a “nature-first” extreme: human inequalities were chalked up to blood and genes.

Fascist ideologies, especially Nazi Germany took Social Darwinist and eugenic ideas to violent conclusions. The Nazis openly preached a doctrine of Aryan racial superiority and enacted policies of racial “purification,” from forced sterilisations to genocide. They justified these atrocities with science about genetics and “blood.” In Nazi propaganda, human worth was rooted in racial biology, compassion for the “weak” was scorned as unnatural. Fascist culture even intertwined this nature-worship with pagan mysticism. Hitler and his inner circle rejected Christian ethics of universal charity as “weak” and sought to revive a quasi-pagan cult of strength and blood. Top Nazi ideologues like Alfred Rosenberg and Heinrich Himmler were bitterly anti-Christian, aiming to “destroy Christianity in Germany…and substitute the old paganism of the early tribal Germanic gods”. The Nazi movement cast itself as a return to ancient warrior virtues, unencumbered by the meekness of modern “slave morals.” In short, the cultural spirit of fascism was deeply anti-egalitarian, it worshipped nature (as they imagined it), glorifying a mythical natural hierarchy of men and races. By 1945, the world had seen the results of the nature-über-alles mindset.

In the economic realm, the unfettered Social Darwinism of early-20th-century laissez-faire capitalism also had run aground with the Great Depression. World War II and its aftermath thus marked a turning point. Biological determinism and scientific racism were thoroughly discredited in the public eye, tainted forever by their association with Nazi barbarism.

Post-War Consensus: Back to Nurture (the Original “Woke” Era)

In the late 1940s and onward, humanity recoiled from the horrors perpetrated in the name of “nature” and race science. The pendulum swung back hard toward environmental explanations. A new orthodoxy took hold across academia, politics, and culture: all humans are fundamentally equal, and observed group differences are due to social context, history, and bias, not biology. This ethos was buttressed by the work of scholars like anthropologist Franz Boas, who had spent the early 20th century debunking claims of fixed racial traits. Boas’s studies showed, for example, that something as “biological” as skull shape could change within a single generation of immigrants due to nutrition and environment, undermining rigid racial typologies. He and his students (like Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict) emphasised culture over heredity, arguing that behaviour and ability are moulded by upbringing and societal expectations, not encoded in DNA. These ideas, once radical, became mainstream after WWII.

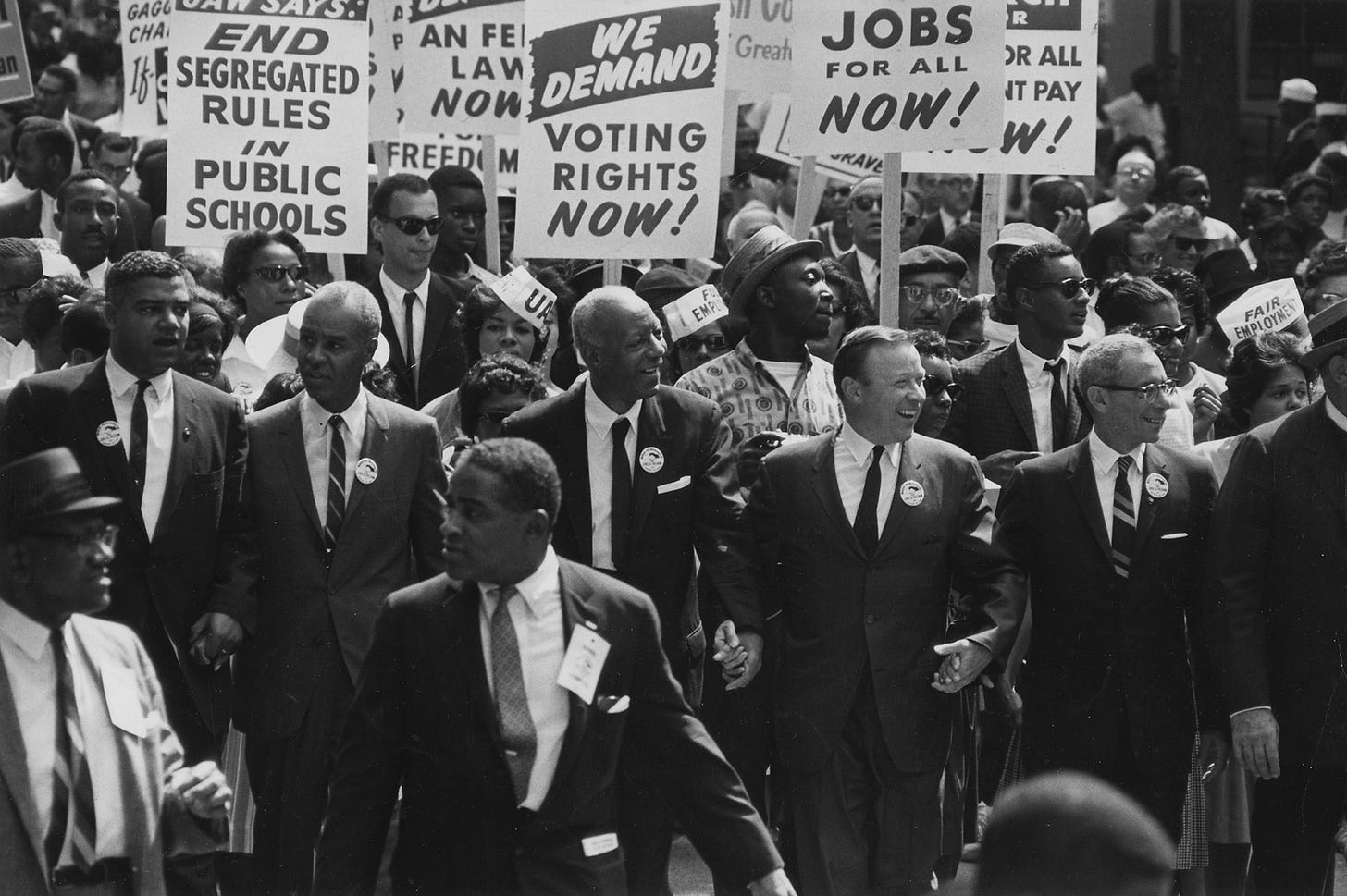

By the 1960s, environmental determinism in the form of racial egalitarianism was driving real-world change. The Civil Rights Movement in the United States, for instance, was predicated on the belief that given equal rights and opportunities, racial groups would achieve equal outcomes. Legal barriers fell: segregation was outlawed, voting rights secured, overt discrimination made illegal. In the decades that followed, more subtle policies aimed to proactively erase outcome gaps, from affirmative action in universities and workplaces to the doctrine of “disparate impact” in law, which treated even race-neutral practices as suspect if they ended up producing unequal results. Institutions sometimes even relaxed standards (for college admissions, job tests, etc.) in efforts to boost minority representation, operating under the assumption that past bias or disadvantage was the only reason for lower average scores, and that adjusting criteria would level the playing field.

By the late 20th century, this outlook was nearly sacred in mainstream discourse, a “liberal absolutism” about human equality. Suggesting innate group differences became taboo, a fast track to public vilification. Society at large was in what you might call a proto-woke mode, highly sensitised to fairness and determined to level playing fields. And indeed, tremendous progress was made in dismantling explicit discrimination. By the 1990s, overt racist or sexist policies were mostly gone, and previously excluded groups had greater opportunities than ever before.

And yet, as the 21st century approached, many outcome gaps had not disappeared. Decades after legal segregation ended, Black and Hispanic Americans on average still had lower incomes and wealth, higher incarceration rates, and other disparities compared to whites. (For instance, in 2016 the median white family in the U.S. had nearly 10 times the net worth of the median Black family.) Women were entering the workforce and leadership in record numbers, but some fields remained male-dominated. Globally, post-colonial countries that were expected to rapidly catch up economically often did not. These stubborn inequalities were vexing to those who expected the post-war reforms to produce uniform outcomes. By the 2010s, a sense of frustration, even betrayal, pervaded progressive circles: We banned the discrimination, we invested in education and anti-poverty programs, yet full equality still hasn’t been achieved. Why?

For many on the left, the answer was that racism and sexism must still be lurking in ever more insidious forms. The late 2010s thus saw the rise of what we now call the Woke movement, essentially a furious effort to root out the remaining (largely invisible) barriers to perfect equality. In a sense, this was the last stand of the post-war nurture-first paradigm: a belief that if equality of outcome hasn’t arrived, it must be because society is still somehow rigged and therefore a more radical cultural revolution is needed.

The Woke Climax (2016–2020): Witch Hunt for the Phantom Menace

Rather than re-examine the assumption that only environment matters, many progressive activists doubled down. If glaring disparities still existed in 2016, the thinking went, the cause must be deeper, more insidious forms of racism and oppression permeating the culture. Thus began the chapter we now know as the Woke era, roughly 2016 through 2020, marked by an intense, sometimes fanatical, effort to ferret out every last vestige of prejudice or “unearned privilege” in our society. This period was essentially a frantic search for a phantom menace, unseen, systemic bias so ingrained that only a kind of ideological witch hunt could smoke it out.

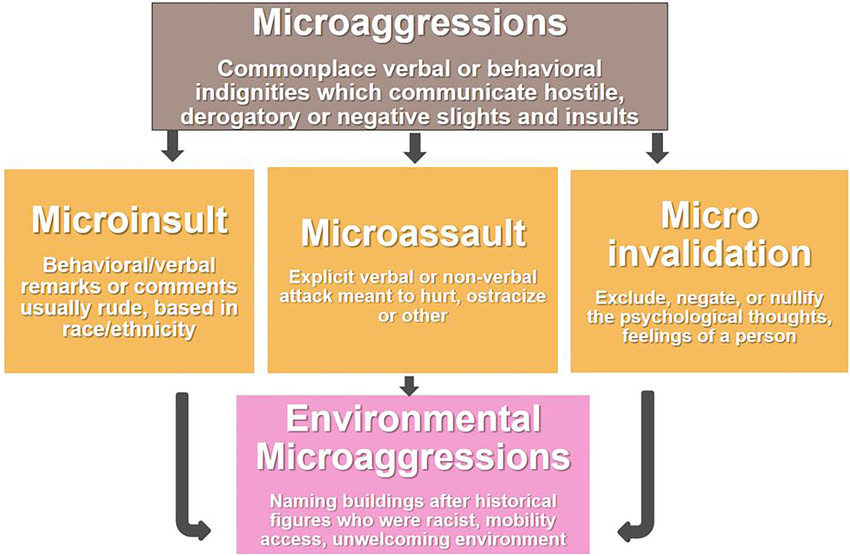

During these years, everyday interactions and language fell under a microscope. Offices and campuses instituted training sessions on “microaggressions,” teaching people to agonize over subtle phrases or biases that might offend. In casual conversation, saying “Where are you from?” or complimenting someone’s hair could be flagged as a microaggression, evidence of implicit prejudice. An expansive new lexicon of social justice etiquette emerged, and policing speech for perfect adherence became routine. Simultaneously, “cancel culture” took off: public figures, professors, even random individuals could face mass outrage and career-ending condemnation if they deviated from the prevailing orthodoxies on race, gender, or sexuality. No one was too famous or obscure to be called out. The atmosphere in progressive circles grew authoritarian in its zeal, dissent from the new dogma (even in nuanced or well-intentioned ways) was treated as heresy that must be stamped out to purify the community.

The Woke movement also turned its eyes to the past. A society-wide cleanse was in order, any symbol or honorific tainted by historical racism or oppression had to be removed. This fervor led to monument toppling and renaming campaigns across the Western world. In the United States, activists targeted hundreds of monuments, first Confederate statues, then figures ranging from slave-owning Founders to colonisers and missionaries, arguing that leaving them in place glorified white supremacy. City by city, longstanding statues of generals and statesmen were spray-painted, yanked down, or carted off as protests swept the nation in 2020. Even figures like Christopher Columbus, once celebrated as an explorer had their monuments torn down for representing colonisation and genocide. In the eyes of Woke activists, American society (and Western society at large) was built on deep-rooted injustice, and only a thorough cultural purge could begin to right those wrongs.

Protesters defaced the J.E.B. Stuart monument in Richmond, Virginia, during the George Floyd protests of 2020, one of many statues of controversial historical figures vandalised or removed amid the Woke-era drive to purge symbols of racial oppression. Over a hundred Confederate monuments and symbols were taken down across the U.S. that year.

For a moment, this Great Awokening had substantial momentum. Institutions rushed to signal their virtuous alignment with the cause. Newspapers and magazines adopted new linguistic codes (capitalising “Black” but not “white,” for instance). Hollywood scrambled to green-light projects addressing representation. Corporations issued mea culpas and diversity pledges. It felt like a cultural revolution from the top down and bottom up. But after four turbulent years, what had this social exorcism accomplished? By 2020, despite all the diversity training, cancelled comedians, renamed buildings, and toppled statues, the “huge social disparities” that sparked the crusade were largely unchanged, still stark, still present. No amount of chasing microaggressions or rehashing history had magically closed the economic or educational gaps between groups. The Woke era, in a sense, ended in frustration: its believers went looking for a Big Bad, an invisible, structural racism lurking everywhere, and came up empty-handed. The obvious legal and policy reforms had long been enacted; what remained was often intangible or unquantifiable.

Yet, when the dust settled (around 2020), what had all this accomplished? The ostensible goal was to eliminate the racial, gender, and class disparities that persisted. But those disparities hadn’t vanished one bit during the Woke frenzy, they were largely the same as before, sometimes even worsening due to broader economic forces. No amount of Twitter shamings or statue-topplings closed the Black–white wealth gap or the gender STEM gap. It turned out that you can rename all the buildings and ban all the jokes, and people’s life outcomes will still be unequal. The “phantom menace” of ubiquitous oppression proved elusive, you could accuse it, symbolically punish it, but you couldn’t actually grab hold of systemic racism and eradicate it like polio. In hindsight, the Woke movement was, in a way, the left “losing its mind” in an earnest but quixotic quest, an almost religious attempt to exorcise society of sins that, in some cases, were intangible or even imagined.

Indeed, the quasi-religious character of Wokeism has been noted by many observers. The movement had its dogmas, priesthoods, and heresies. It demanded public confessions of privilege, ritual denunciations of blasphemers, and conversions (“allyship”) of the unenlightened. Some commentators explicitly likened Wokeness to Gnosticism, an ancient Christian heresy. Gnostics divided the world into a corrupt material realm and a pure spiritual knowledge (gnosis) accessible only to the elect. Similarly, Woke ideology divided people into the “woke” (those enlightened to the hidden evils of society) and the “unwoke” (those blind to or complicit in oppression). It treated the existing social order as fundamentally oppressive (much as Gnostics saw the material world as evil) and promised a kind of salvation through awareness and activism. This isn’t just a glib analogy, scholars have pointed out that Woke culture’s fixation on invisible power structures and moral purity maps closely onto the Gnostic mindset. Understanding this quasi-spiritual fervour helps explain why the Woke era often seemed impervious to reason or empirical debate: it wasn’t just politics, it was a crusade to expunge wickedness and achieve moral transcendence.

By late 2020, however, a backlash was in full swing. The excesses of Wokeism had begun to generate a fierce counter-movement. On one level, everyday folks were simply exhausted by the humourlessness and hypersensitivity. Satirists and commentators started poking holes in the most absurd parts of Woke culture (like the idea that math is racist or that clapping should be replaced by “jazz hands” to avoid startling people). The term “Social Justice Warrior” (SJW) became a pejorative, and being “woke” went from a proud left-wing label to an object of ridicule in popular discourse. Polls showed increasing numbers of Americans (of all races) felt political correctness had gone too far.

Importantly, within the left itself a schism appeared: more centrist liberals began speaking out against the illiberal tactics of the Woke left, worrying that core values like free speech and individual rights were being trampled. In 2020, a group of prominent writers and academics published an open letter in Harper’s Magazine decrying the “intolerant climate” and calling for a return to open debate – essentially a plea against cancel culture. When even centre-left luminaries like J.K. Rowling and Barack Obama cautioned against Woke extremes, it signalled that the cultural tide was turning.

And turn it did. The Woke era more or less collapsed under its own weight by 2021. After four or five years of moral frenzy, enough people (left, right, and center) said “enough.” Comedians started telling edgy jokes again. People began to admit that maybe intent and context do matter, that perhaps not every unequal outcome is proof of diabolical prejudice. The spell was broken. What had been a roaring blaze of “social justice” activism died down to embers almost overnight. Today, calling someone “woke” is often an insult, implying performative or overzealous virtue-signaling. It’s a remarkable reversal for a movement that, just a short time ago, dominated the cultural landscape.

The Edgelord Era: Enter Genetics (Nature Returns)

So are we now swinging back to the opposite extreme? Many observers believe yes, that we’ve entered an anti-woke backlash era, sometimes labeled the age of the “edgelord” or the new “anti-PC” culture. Superficially, this era is characterised by a return of irreverence, podcasts and influencers gleefully mock Woke pieties, and there’s a renaissance of politically incorrect comedy and commentary. But under that surface is a deeper shift, a growing willingness to question the nurture-only creed that has reigned since World War II. In other words, the door is opening again to arguments about “nature”, genes, biology, and innate differences, as part of the explanation for human outcomes. What was unsayable a decade ago (in mainstream discourse) is now being said, and with increasing volume.

Several signs point to this shift. In science, research on genetic influences in behaviour, cognition, and group differences, long tiptoed around is gaining mainstream visibility. Academics are publishing findings on DNA variants associated with educational attainment, intelligence, personality traits, etc. and getting covered in major media. The idea that there may be average genetic differences (however slight) between populations is no longer absolute heresy, despite still being very controversial. In 2019, author Angela Saini published Superior: The Return of Race Science, documenting how a once-taboo belief in biological racial differences has been creeping back into scientific and public view. And in 2020, a political scandal in the UK underscored the shifting Overton window: an advisor to the Prime Minister had to resign after it came out he’d suggested there are IQ differences between races. The mere fact such an idea had been entertained (even by a rogue advisor) showed that what was formerly unthinkable had, for some, become thinkable again.

We also see a renaissance of old-school anti-egalitarian philosophy in certain corners of the internet. On forums and YouTube, one can find a resurgence of interest in thinkers like Nietzsche (who called equality a morality for the “weak”), or in Social Darwinist ideas rebranded as “HBD” (human bio-diversity). Communities discuss topics like evolutionary psychology and population genetics frankly, sometimes veering into pseudoscience, but also sometimes just exploring legitimate research that would have been shouted down in earlier years. The point is, biology is back on the table in a way it hasn’t been for a long time.

This counter-cultural shift isn’t occurring in a vacuum, it’s fuelled in part by the failures of the Woke era. Woke activists had confidently insisted that all group disparities must be caused by discrimination or bias. They aggressively suppressed any other hypotheses. But when their social crusade didn’t magically equalise society, people began to reconsider that assumption. A new generation is asking: what if some differences do have a biological component? What if the 70-year project to remould human nature hit natural limits? These questions are uncomfortable, even dangerous in their potential misuse, but they’re arising nonetheless. Influential scholars and public figures (even some with liberal credentials) are cautiously broaching topics like innate cognitive ability, heritability of traits, and sex differences in ways that would have been career-ending not long ago. The pendulum that once swung firmly to “it’s all environment” is moving toward “maybe it’s also genes.”

Alongside the scientific and intellectual shift, there’s a broader cultural counter-revolution brewing. After the perceived excesses of woke progressivism, many people, especially young people are embracing values and identities that would have been considered reactionary not long ago. For instance, there’s a mini-revival of traditional religion and traditional gender roles among some Gen Z and Millennial groups. In an ironic twist, being a conservative Christian or a proponent of old-fashioned family values is edgy to youth in certain subcultures now, a rebellious stance against the secular liberal mainstream. Surveys have noted a small but significant uptick in young adults expressing interest in traditional Christianity and public affirmations of faith, bucking a long trend of secularisation. Culturally, things like modest fashion, homemaking, and large families, once derided as relics have garnered fresh appeal in niches of social media. It’s as if, having seen the fruits of hyper-progressivism, some are yearning for the perceived stability of tradition.

Even more striking is the rise of an intellectual movement outright rejecting Enlightenment egalitarian ideals. Often dubbed the “neo-reactionary” movement or “Dark Enlightenment,” it’s a loosely knit community of bloggers and thinkers who argue that democracy, equality, and liberalism have failed and that we should return to older forms of hierarchy and authority. They celebrate explicitly anti-egalitarian ideas, for example, that natural aristocracies (whether based on IQ, strength, or other traits) should rule, that some races or cultures are better suited to leadership, and so forth. This was fringe in the early 2000s, but by the late 2010s it gained traction among some tech and academic circles. The Dark Enlightenment advocates a return to “traditional societal constructs” and even flirts with monarchism; it is openly reactionary, calling liberal modernity a wrong turn.

All of this points to a emerging Social Darwinism 2.0. The intellectual mood music has distinctly changed. We are seeing the contours of a narrative that says: The Woke experiment failed because it tried to force artificial equality against hard biological reality. To truly understand society (and fix it), we must acknowledge natural differences, even if it’s uncomfortable. In this view, the post-WWII assumption of human interchangeability was naive, and the future will involve integrating facts about genetics into policy rather than denying them. It’s a controversial stance but it’s increasingly part of the conversation.

History’s Pendulum:

So, to return to the question: are we about to get a sequel to Woke? The likely answer is no, we’re in for something else. The pattern of history suggests that after an era obsessed with one explanation (in this case, environment), we get an era obsessed with the opposite (genes). It’s less a simple back-and-forth repeat of Woke vs. anti-Woke, and more a grand pendulum that takes decades to arc from one end to the other. The Woke era was the culmination of a 70-year swing toward nurture-first thinking. The Edgelord/anti-woke era we’re entering appears to be the start of a swing back toward nature-first thinking. In time, that swing too will have its excesses and tragedies and no doubt, generations from now, there will be another corrective swing to re-emphasise human equality and social factors.

As of 2025, that pendulum is unmistakably on the move. The sequel to Woke will not be “Woke 2.0”, it will be a counter-reaction on a deeper level. We should expect new debates, uncomfortable conversations, and likely a whole new set of social conflicts as the old consensus cracks. For those who grew up believing in a steady march of progress toward greater equality and enlightenment, the coming years might feel like whiplash. But in the grand cycle of ideas, what’s old becomes new again. Woke thought didn’t vanish, it’s just becoming unfashionable, waiting for its turn to cycle back in the future. In the meantime, its opposite is taking centre stage. History, it seems, doesn’t move in a straight line, it oscillates. And we’re about to find out what the next swing brings, for better or for worse.

This is a great historical essay. I wonder how Donald Trump fits into this analysis.

Excellent analysis, Celina. The more I study history the more I realize that the skeletal framework of the Hegelian dialectic is ultimately true, even if Hegel’s presuppositions and conclusions are not. There does seem to be an archetypal, perennial (perhaps metaphysical) phenomenon that maps itself on to each historical era.